The Alabama Solution is Modern-Day Slavery

A closer look at the case exposing government-sponsored slavery in Alabama’s prisons.

In Alabama, incarceration is a business—and prison labor is at its center. In pursuit of cost-cutting and profit-making, government agencies, fast food chains, auto manufacturers, and others have knowingly participated in and perpetuated a modern-day forced labor scheme through the state’s carceral system. Under the scheme, the state of Alabama coerces incarcerated people under threat of violence into working free—or for as little as 25 cents an hour—while their parole is frequently denied or delayed to keep them on the job.

The way Alabama’s forced labor scheme operates is ruthlessly simple: Incarcerated people must work or suffer violent consequences. A discriminatory parole system keeps them incarcerated not for public safety, but so the state can exploit their labor for the financial benefit of public agencies and private businesses.

The Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) has created and maintains the most brutal and deadly prison system within the United States. Incarcerated people within the walls of ADOC facilities regularly must choose to work or face brutal and often deadly violence. This power imbalance gives the private and state employers who “lease” their labor from ADOC every advantage. Forced prison laborers arrive at their worksites with the carceral boot on their necks, without the freedom or ability to bargain or protest working terms and conditions.

From the time of chattel slavery to the post-Civil War convict-lease system to the Jim Crow era, the state of Alabama has built its economy on the back of a commodified, coerced, and racist labor system. Today’s prison labor scheme is that long history’s most recent iteration.

In December 2023, Justice Catalyst Law filed a class-action lawsuit, Council, et al. v. Ivey, et al., on behalf of current and formerly incarcerated Alabamians, two of the largest labor unions in the U.S., and an Alabama civil rights organization. The suit alleges that Alabama coerces the people in its prisons into working for state and private actors under threat of violence in order to benefit government agencies and private corporations. Relying on the state’s own data and records, the suit explains that Alabama’s scheme targets people with the best training, work, and disciplinary records for parole denial so that the state and its private sector partners can keep profiting off forced labor.

By those same metrics—years of working reliably alongside free workers in the community—these are people who have proven time and again that they should be released, and use their labor to support their families and communities.

This system deems incarcerated people too dangerous to be set free, yet they’re safe enough to work in the community, unsupervised, next to free workers in a fast food chain, or a poultry processing plant, or a car parts factory—with the ADOC taking a 40% cut from their gross wages. And when those incarcerated people work for the ADOC itself inside its facilities as guards and prison staff, which, the suit explains, they’ve done for more than a decade, they receive no wages at all.

The plaintiffs accuse defendants, which include Alabama Governor Kay Ivey, Attorney General Steve Marshall, and the state’s Bureau of Pardons and Paroles, in addition to private actors like Burger King and Bama Budweiser, of violating federal trafficking, racketeering, and equal protection laws, such as the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, among others.

The lawsuit takes a big swing at the system. The suit connects the dots between the physical and psychological violence of Alabama’s carceral system and the financial exploitation of a disproportionately Black incarcerated population. It aims to dismantle Alabama’s forced labor scheme, return all profits from labor to the laborers themselves, and ensure the parole of thousands of qualified, safe, and trained incarcerated workers who should have been returned to their communities and reunited with their families years ago.

The time that’s been stolen from these individuals and their families can never be restored, and the stakes for those still inside the system are life and death.

laying the foundation

laying the foundation

Present Day

WHY WE’RE HERE

WHAT’S NEXT

HISTORY & CONTEXT

Alabama’s history of systemic racism, from Reconstruction to present day

Enslaved Black people were the labor force that fueled Alabama’s original agriculture-based economy, cultivating the cotton cash crop in the 18th and 19th centuries before it was exported around the globe.

When Alabama seceded from the Union in January 1861, its population was just shy of one million, and 44% of that population was enslaved.

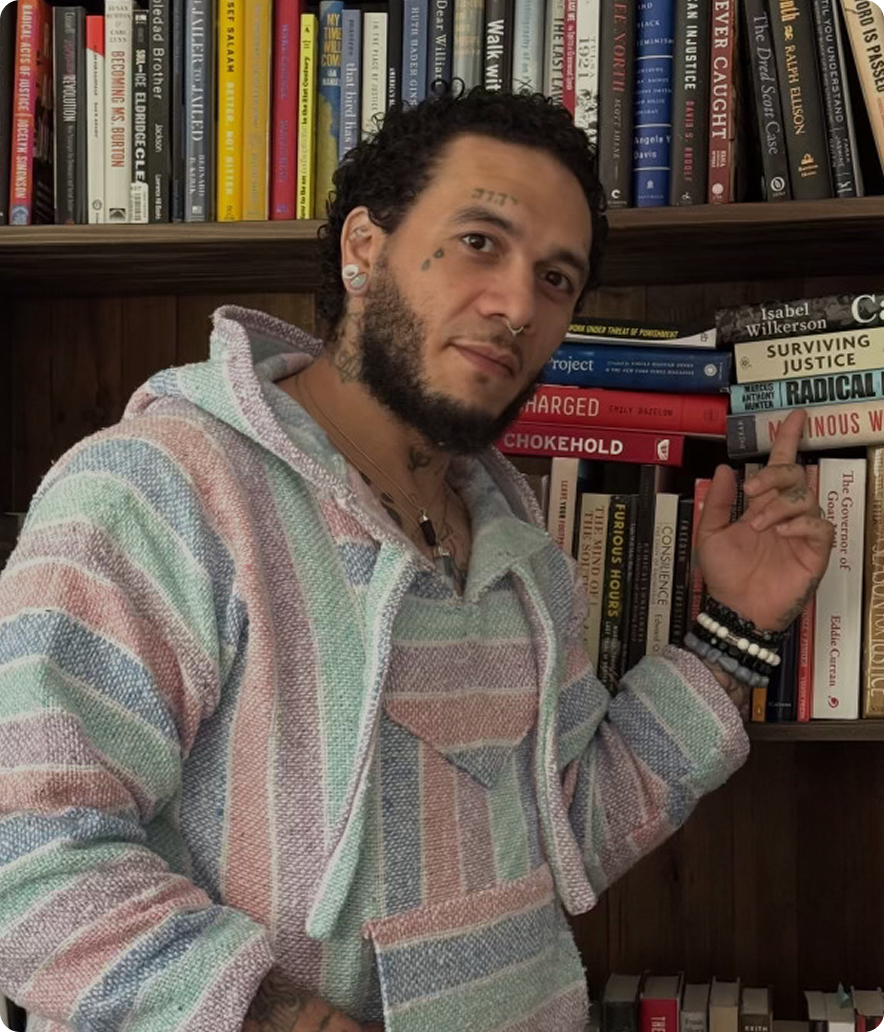

ROBERT EARL COUNCIL

AKA “KINETIK JUSTICE”

Read his claim in the lawsuit

“

“When did slavery end in Alabama? And that’s not a rhetorical question. Alabama is still partaking in slavery today. … People, right now, are being forced to work for free while someone else reaps the benefit from their profits.”

—Plaintiff Robert Earl Council, aka “Kinetik Justice”

At the end of the Civil War in 1865, lawmakers ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, abolishing the practice of slavery—“except as a punishment for crime.” This left a loophole that former enslavers and slave states exploited with abandon, immediately arresting former slaves en masse and thereby replacing slavery with debt peonage and convict-leasing.

The Reconstruction-era convict-lease system, a precursor to what is seen today in Alabama’s carceral system, let private companies and individuals pay the state in exchange for incarcerated people’s labor. The system formally lasted from 1875 to 1928, and powered the state financially.

THE MONEY

The financial motivation behind Alabama’s forced labor scheme

Like slavery before it, the present-day forced labor scheme in Alabama is rooted in systemic racism and power, but greed is the engine that drives it forward.

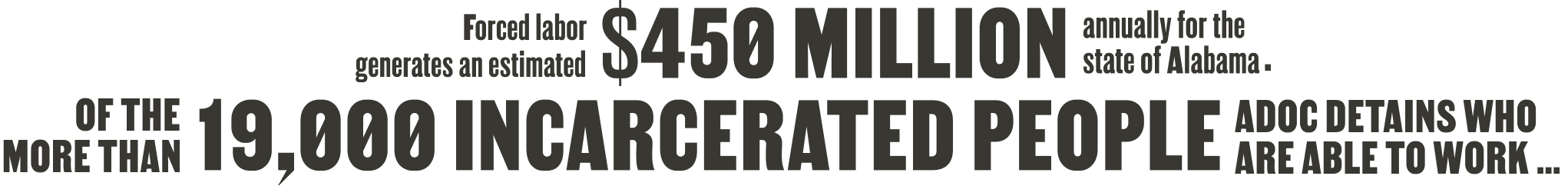

Alabama enjoys an estimated $450 million, minimum, in annual benefit from exploiting incarcerated workers under the forced labor scheme. In FY2024, the ADOC reported a $12.2 million profit from its “work release programs” alone, made up of the 40% cut it took from the gross wages of every incarcerated worker, which operates as Alabama’s human trafficking fee.

ARTHUR CHARLES PTOMEY

Read his claim in the lawsuit

Across its own system, ADOC relies on unpaid incarcerated labor to maintain its facilities, filling roles like guards, drug counselors, medical assistants, and other staff.

Public employers, including the City of Montgomery and the Alabama Department of Transportation (ADOT) secure far greater wage savings than private employers, as they’re required to pay “leased” incarcerated ADOC laborers at most only 25 cents an hour and a maximum of $2 per day.

“

Each corporation, each fast food company, anybody who participates and has their hand in the cookie jar with the Alabama Department of Corrections, is guilty of slavery.

—Plaintiff Robert Earl Council, aka “Kinetik Justice”

Private employers who lease laborers from the ADOC’s “work release” system technically are obliged to pay the community’s prevailing wage for that job. Though many actually pay far less, the illegally low wage is not what attracts private employers—they’re drawn to the financial gain that comes with all forced labor: Through leasing workers from the ADOC, private employers secure a fully coerced workforce—people who cannot speak up, defend, or bargain for themselves to secure wage, safety, or other rights that protect free workers from workplace abuses.

Over 10,000 individuals have been put into ADOC’s work release program since 2018, according to an AP report, collectively logging over 17 million work hours. Under that program, about 575 private corporations in industries including automobile manufacturing, poultry processing, and fast food chains, like McDonald’s and Burger King, have used incarcerated labor. About 100 public entities at the city, county, and state level have also relied on incarcerated workers. In February 2025, nearly 1,500 incarcerated people were in the work release program, an additional 1,800 were working for public entities through the ADOC’s work centers, and tens of thousands of incarcerated people are working directly for ADOC, propping up the prison itself with unpaid labor coerced with threats of violence.

Present Day

laying the foundation

Present Day

WHY WE’RE HERE

WHAT’S NEXT

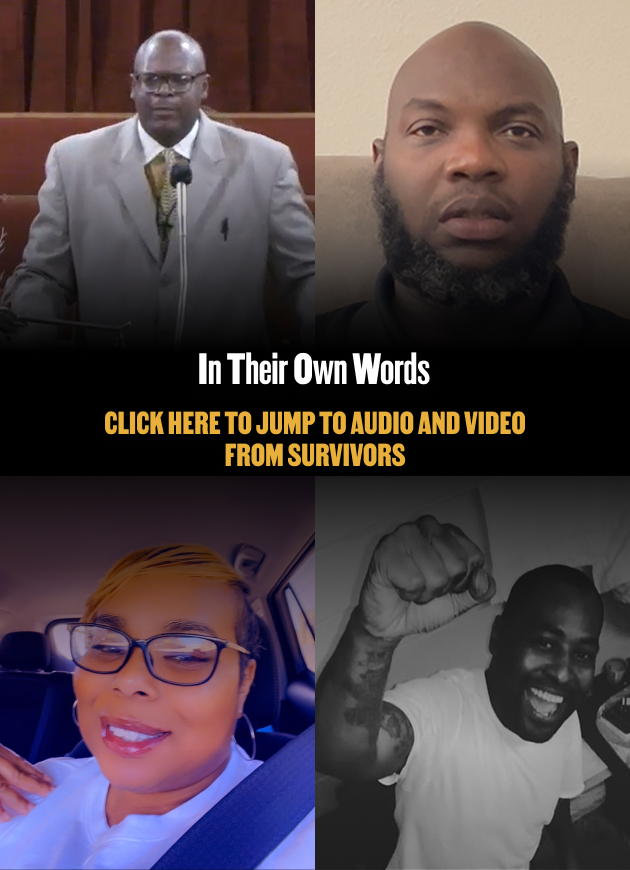

THE PLAINTIFFS’ STORIES

What life is like inside Alabama’s prison system

At the time plaintiff Alimireo English requested to be transferred to Ventress Correctional Facility’s Faith Dorm, he had seen and experienced unspeakable violence at ADOC’s hands. As he detailed in the Plaintiff’s Complaint [warning, the content he describes is disturbing and graphic], he both attempted to prevent the continued assault against a fellow incarcerated person and reported it, acts for which he was punished. ADOC failed to act, and the person was ultimately murdered.

English was overdue for release. He had been tried and acquitted by a jury of the charges by which his parole had been revoked—an employer’s false complaint to cover her own illegal activities—but the ADOC continued to hold and compel him to labor. English remained in prison for two years after his acquittal, becoming one of thousands kept by Alabama in prison because their labor is too valuable and profitable to give up.

JEREME APPRENTICE COLE

Read his claim in the lawsuit

After the Parole Board revoked his parole, English was “hired” to work in the Faith Dorm—without any pay—becoming the custodial supervisor for 190 people, many of whom were elderly and disabled. In addition to his 12-15 hour shifts, English had to be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“I have endured and witnessed the exploitation of the rehabilitated, trustworthy, and model inmates throughout my 13 years of maneuvering through ADOC,” he said. “Inmates and maintenance have keys to gates and doors, work 12 to 14 hours, and [will] still be on call, getting paid only peanut butter jelly sandwiches, and leftovers from their supervisor’s lunch.”

He was finally granted parole in December 2024 and released in April of 2025.

Within ADOC’s facilities, incarcerated people have been actively fighting to protect their human and civil rights. The Free Alabama Movement (FAM), a nationwide prison organizing group, called and expressed support for strikes in 2014, 2016, and 2022, both within Alabama and in other states. FAM’s largest strike, in 2016, mobilized a reported 24,000 incarcerated people across the country, making it the largest prison work stoppage in U.S. history. On September 26, 2022, people from all 13 Alabama correctional facilities refused for many weeks to continue the forced labor required of them by Alabama to demand better conditions, fewer parole denials, and higher pay.

FAM founder and leader Robert Earl Council, known as “Kinetik Justice,” has been incarcerated since 1995. Kinetik is an outspoken advocate for incarcerated people’s rights and the use of nonviolent means to fight the carceral system’s forced labor regime and other abuses.

Hundreds of family members and supporters gather in Montgomery, Ala. to hold a Vigil for Victims of Alabama Prisons on March 7, 2023

Hundreds of family members and supporters gather in Montgomery, Ala. to hold a Vigil for Victims of Alabama Prisons on March 7, 2023

Frederick Denard McDole

ADOC has brutally punished Kinetik for his activism: five years of solitary confinement, beatings, harassment, and psychological abuse. In 2021, ADOC personnel beat Kinetik so badly he sustained permanent brain injury and eye trauma that permanently impaired his vision. Even so, he has continued to fight against Alabama's modern slave system and also for basic rights and dignity within the ADOC and beyond.

Following retaliation for exposing a gambling ring within ADOC facilities in 2019, Kinetik said in a statement to Shadowproof: “I don’t bend, fold, or break. I’m Kinetik, my mama didn’t raise no quitters. Still standing strong, I remain!”

Alabama’s prison system is the deadliest in the nation. The per capita homicide rate is 73 per 100,000 people, according to a February 2025 report from the ACLU. That figure is nearly 10 times Alabama’s homicide rate and almost 11 times the national average. Stabbings, rape, sexual assault, acid attacks, beatings, and food deprivation are also routine, according to reports from both incarcerated people and prison staff.

Frederick Denard McDole

Two systemic factors drive violence within ADOC facilities: understaffing and overcrowding. In FY2018, the ADOC reported 1,072 security staff on its payroll, down 1,843 from FY2014—despite ADOC’s authorization to employ 3,326 correctional officers. Staffing numbers have failed to increase substantially to date, as confirmed in Braggs v. Dunn, where the federal court found that the understaffing crisis “poses a substantial risk of serious harm,” and the most recent status report confirmed that ADOC continues to operate at dangerously low staffing levels, far below what is required for constitutional compliance.

The prison population, meanwhile, is well over capacity. An ADOC report from June 2025 states that its facilities can accommodate 12,115 people, but the current prison population stands at 21,044. To put it another way: As of 2024, the state incarcerates 898 people per 100,000. If it were its own country, that would put Alabama in sixth place for global incarceration rates.

The U.S. Department of Justice has likewise documented the ongoing crisis. As its United States v. State of Alabama and Alabama Department of Corrections complaint, filed December 9, 2020, explains: “Alabama’s prisons for men are now more overcrowded than in 2016, when the United States initiated its investigation, prisoner-on-prisoner homicides have increased, prisoner-on-prisoner violence including sexual abuse remains unabated, the physical facilities remain inadequate, use of excessive force by security staff is common, and staffing rates remain critically and dangerously low.”

LAKEIRA WALKER

Read her claim in the lawsuit

Working for 12-hour shifts in a meat warehouse kept between 30 and 40 degrees without sufficient clothing took a physical and mental toll on Lakeira Walker. But she and the women around her had no choice.

“

Officer said ‘Hey, Walker, you gotta get up and go to work. Make us all 40%,’ and I was like, ‘I can’t even move.’

Alimireo English

Read his claim in the lawsuit

Plaintiff Alimireo English, who was given life plus 40 years for possession of two ounces of cocaine, walks us through the circumstances that led to the violation of his parole, his acquittal, and the repeated parole denials he faced afterwards.

“

I felt like I was going to be given an opportunity to start my life over.

THE PAROLE CRISIS

How Alabama’s parole board fueled a racist, forced labor system

In the mid-2010s, Alabama’s prison system was reaching a boiling point. The state had the most crowded prison system in the U.S., operating at 195% capacity.

These numbers spurred criminal justice reform. In May 2015, Alabama enacted Senate Bill 67, or the Justice Reinvestment Act (JRA), designed to address overcrowding by reducing recidivism rates and implementing evidence-based standards for the state’s Bureau of Pardons and Paroles.

LEE EDWARD MOORE, JR.

Read his claim in the lawsuit

From FY2015 to FY2018, parole grants rose from 38% to over 53%, and the prison population dropped from 24,191—nearly hitting a 4,200 reduction goal set by the state. In addition, near racial parity was reached in parole rates between Black and white applicants.

But progress was short-lived. The newly-inaugurated Governor Kay Ivey championed new legislation in 2019 that increased the governor’s power over the Board, allowing her to shut down the parole system and capture the labor force she needed to keep ADOC running.

Under Ivey’s leadership and direction, parole hearings slowed dramatically. From FY2019 to FY2020, only 2,704 parole hearings were held—down from 4,270 in the previous year—and only about 20% of applicants were granted parole. The parole grant rate for those convicted of violent crimes dropped from 44.7% in FY2018 to just 3.5% in FY2022.

Alabama’s parole grant rates for Black incarcerated people plummeted from around 50% in 2018 to just 6% in 2022. By that year, white incarcerated people were more than two times more likely than Black incarcerated people to be granted parole. Data from that time also shows that Black incarcerated people convicted of a “violent” crime were also less likely to be granted parole than white incarcerated people, with the former standing at a 2.2% parole grant rate in FY2022, and the latter at 4.9%.

“They gotta keep me for another year until they can find somebody else on the street that they can pull back in and take my place,” Alimireo English said in an interview with In These Times. “If they can’t replace you, they don’t let you go.”

The Parole Board’s anti-parole standards, framed under the pretext of “public safety,” effectively kept its incarcerated labor pool trapped in the system.Those most eligible to receive parole found that their clean disciplinary records and good behavior only served to identify them as an ideal candidate for the prison system’s forced labor scheme.

WHY WE’RE HERE

laying the foundation

Present Day

WHY WE’RE HERE

WHAT’S NEXT

The lawsuit

What you need to know about Council v. Ivey

Council v. Ivey seeks to send people home, putting the money they earn from their labors back into supporting their kids, families, and communities, and end an illegal practice once and for all.

The class action lawsuit filed in December 2023, Council, et al. v. Ivey, et al., aims to take down Alabama’s “modern-day form of slavery.” Filed by Justice Catalyst Law, the suit’s unprecedented scope includes current and former incarcerated Alabamians, two major labor unions, and a civil rights organization and takes a broad, federal-level approach to end the state’s carceral forced labor and human leasing scheme.

MICHAEL CAMPBELL

Read his claim in the lawsuit

The suit alleges that Alabama runs a modern-day, racially-biased “convict leasing” system—especially targeting Black incarcerated people—that coerces cheap or free labor from the prison population through threat of violence in the state’s notoriously deadly prison system, and through systematic parole denial.

The conspiracy, the suit alleges, includes local governments like the City of Montgomery and Jefferson County and private enterprises like Burger King, Wendy’s, McDonald’s, and Bama Budweiser as defendants, but also Alabama Governor Kay Ivey, Attorney General Steve Marshall, and the powerholders on the Parole Board. These defendants, the suit argues, have knowingly perpetuated the scheme in order to fill private and public coffers. Since 2018, according to the complaint, about 575 private enterprises and over 100 public entities have exploited incarcerated workers, with Alabama alone enjoying an estimated $450 million in annual benefit.

It seeks to demonstrate that racially discriminatory parole delay and denial, in addition to endemic violence within the prison system, have been essential to maintaining the labor pool for the scheme. As the complaint explains, the Parole Board “effectively and systematically altered sentences … substantially increasing the risk that incarcerated people, particularly Black people, eligible for parole would be subjected to extended confinement … with the foreseeable and intended effect of maintaining a large, incarcerated, and disproportionately Black workforce.”

The case charges that the defendants have not only violated the Alabama Constitution—which was amended in 2022 to officially ban all forms of slavery and involuntary servitude—but also the U.S. Constitution and a number of federal statutes, including those that prohibit racketeering (under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, “RICO”), trafficking (under the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, “TVPA”), and race discrimination (under the KKK Act).

The suit seeks to have the scheme dismantled. It also calls for Alabama to set free thousands of people long eligible and qualified for release back to their communities and families. Further, it demands that defendants cease compelling and participating in forced labor and asks that they disgorge their profits from the convict leasing scheme.

The ripple effect

The labor union and civil rights plaintiffs

Two major labor unions in the U.S.—the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, Mid-South Council (RWDSU) and the Union of Southern Service Workers (USSW)—joined Council v. Ivey as plaintiffs, demonstrating the impact that the forced labor scheme had not just on incarcerated individuals, but also on Alabama’s labor market as a whole. The result is a race to the bottom in the market’s wages and conditions, particularly for Black workers. Free Alabamian workers must compete with trafficked, incarcerated laborers paid the lowest-possible wages.

Members of the RWDSU and USSW work alongside incarcerated workers at various private companies in Alabama, including in the poultry processing and fast food industries. Both unions argue that the use of coerced labor has a downward effect on wages, benefits, and working conditions for their members. Given the danger of retaliation and discipline, incarcerated workers are unable to freely advocate for better wages and conditions, undermining the process for unionized workers. That, in turn, weakens the leverage their members have to organize and bargain for fair contracts.

“

We will not look away. We demand that the corporations benefiting from this corrupt and racist scheme be held accountable and that they do what justice requires: Hire workers as free people, with fair pay and the basic protections every worker deserves

Stuart Appelbaum, President of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU)

“The RWDSU is unwavering in our commitment to end modern-day slavery in Alabama—and to root out this vile exploitation wherever it exists. Forced labor for profit has no place in a just society," says Stuart Appelbaum, president of the RWDSU. "We’ve fought for generations to confront economic and racial injustice, but this makes clear how much more work remains. The RWDSU’s mission has always been grounded in one simple truth: every worker deserves respect, dignity, and freedom. Yet today, more and more—overwhelmingly Black—Alabamians are being forced into labor, stripped of their rights, and denied their humanity. That is unacceptable. We will not look away. We demand that the corporations benefiting from this corrupt and racist scheme be held accountable and that they do what justice requires: Hire workers as free people, with fair pay and the basic protections every worker deserves."

What's Next

laying the foundation

Present Day

WHY WE’RE HERE

WHAT’S NEXT

What's next

Where Council v. Ivey stands now

Since Council v. Ivey was filed in December 2023, The New York Times has covered the lawsuit, in addition to The Washington Post, NPR, and Bloomberg. In 2024, the Associated Press published an independent investigation and longform report on Alabama’s prison system and use of forced labor.

Some of the abuses detailed in the lawsuit have also made their way to the big screen. The Alabama Solution, a 2025 HBO documentary film, shines new light on the realities of Alabama’s prison conditions from the perspective of those incarcerated. Co-directed by Emmy and Peabody Award-winning director Andrew Jarecki and documentary filmmaker Charlotte Kaufman, The Alabama Solution premiered at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival and won critical and audience acclaim. It was released on HBO on October 10, 2025

“

Why would the slavemaster, by his own free will, release men on parole who aid and assist them at making their paid jobs easier and carefree?

—Plaintiff ALIMIREO ENGLISH

Though Council v. Ivey has yet to go to trial, the case has already had an impact in Alabama. Immediately after the lawsuit’s filing, the Parole Board admitted that there were systemic errors as to parole reset dates for a number of plaintiffs; then in June 2025, Parole Board chair Leigh Gwathney’s term ended without renewal. Her tenure had been rife with criticism—most of which tracked the complaints and data made public by plaintiffs in the Council v. Ivey filings. Governor Ivey replaced Gwathney with law enforcement officer Hal Nash, and parole rates have risen by close to 67% as of August 2025—the highest rate since 2019, according to Parole Board statistics.

The case is still in the early litigation phase, pending before the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama. Plaintiffs filed an amended complaint in May 2025, expanding the named plaintiffs from 10 to 20 and providing extensive additional details regarding the systemwide violence the plaintiffs endured as part of the scheme to compel their labor. Currently, the parties are litigating pleading motions raised by defendants which, once resolved, would allow the case to move forward to the discovery phase, where crucial information on the ADOC’s forced labor scheme, previously unavailable to the public, can be brought to the court’s scrutiny.

“This system is pervasive, and it is tragic,” said Benjamin Elga, founding executive director of Justice Catalyst Law. “But here’s the thing: Systems like this are built in the dark. They grow and take hold when they’re left in the dark. But when we shine a light on them, we expose them and we can defeat them.”

It won’t be easy work. As plaintiff Alimireo English, previously incarcerated in Alabama’s prison system for 13 years, said: “Why would the slavemaster, by his own free will, release men on parole who aid and assist them at making their paid jobs easier and carefree?”

laying the foundation

Present Day

WHY WE’RE HERE

WHAT’S NEXT

More than JUST NUMBERS

What life is like inside Alabama’s prison system

Using violence, ADOC compels

3,000

Forced laborers to work for private companies and public agencies across Alabama

Spanning a wide range of industries—from fast food to the auto supply chain, alongside more than 50 state and local government agencies—private and public employers across Alabama pay the state millions to secure a fully coerced workforce who can't secure even basic workplace safety and wage protections.

Alabama secures millions in benefits FROM

1,000

Forced Laborers Each Day Building Furniture and Goods for Government Use Statewide

In ADOC's Correctional Industries, incarcerated people are compelled to work every day, all day, in a variety of skilled jobs for pay of no more than 25 cents an hour building furniture, maintaining the state's vehicles, and manufacturing a wide range of goods used by state and local government staff statewide, including the Supreme Court of Alabama.

Through violence, ADOC compels

15,000

incarcerated people to run and maintain its prisons every day, all day, for zero pay

Forced unpaid labor performs every conceivable job without pay across ADOC's statewide prisons, from dorm supervision to medical assistants to building construction to running drug rehab and educational facilities.

Read more

Green et al. v. Massachusetts Department of Corrections et al. (2021)

After a year-long investigation by JCL, in 2021, people incarcerated in Massachusetts, represented by Justice Catalyst Law and BraunHagey Borden, filed two lawsuits, one in Massachusetts state court against the Massachusetts Department of Corrections (DOC) and one in federal court ...Read more

Tassinari v. The Salvation Army et. al. (2021)

In 2021, after many months of investigation by JCL involving locating and interviewing hundreds of unhoused people living with opioid disorder across the country, JCL and the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund filed, and were later joined by...Read more

Moerhl v National Association Realtors (2019)

In 2024, JCL and national firms Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC (“Cohen Milstein”), Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP (“Hagens Berman”), and Handley Farah & Anderson (“HFA”), secured a ground-breaking resolution of the 2019 class action suit filed on the heels...Read more

518.732.6703

Justice Catalyst Law is a registered 501(c)(3) organization

Terms of Use | Privacy Policy